Plattsburgh Shock Therapy: Urban Renewal Like It's 1955 (Part 3)

This is part 3 of a 3 part series: Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3

"Nobody but charlatans can be prophets and everybody can be as aware as possible of what is actually happening."

"Nobody but charlatans can be prophets and everybody can be as aware as possible of what is actually happening."

Adventures in Maldevelopment

There's a big problem with the governor's newfound interest in urban revitalization aside from its blatant disregard for social justice and democracy: Just like urban renewal decades prior, attempting to revitalize cities and return them to solvency by concentrating on large projects that are quickly built to a finished state rather than small projects that develop incrementally over time is a recipe for failure.1Simplicity versus Organized Complexity

First, large-scale developments that are built all at once rely on oversimplified projections that cannot adequately account for the organized complexity that characterizes cities. This is the point of Jacobs' phrase "nobody but charlatans can be prophets." As Jacobs showed in Death and Life of Great American Cities, a book published in 1961 and still ahead of its time for present-day Plattsburgh, even the success of seemingly simple things like parks and sidewalks depend on many factors all around them working together in concert reinforcing each other. A safe sidewalk, for example, requires that people use it at all times of the day; people are more likely to use the sidewalk at various times throughout the day when they know there are "eyes on the street," that is, people regularly entering and exiting places of business, people sitting in benches or people looking onto the street from upper floor apartments watching passersby. Yet, there are more likely to be eyes on the street when there are interesting things like people walking on the street to watch. In the absence of such self-reinforcing factors, streetscapes and parks tend to become dead zones.

This is why large-scale projects, which attempt to build entire sections of cities all at once, can easily go awry. For this reason, Jacobs-inspired planners prefer to develop incrementally, building off of what is working and "what is actually happening." They look for existing "desire paths" and experiment with temporary pilot projects before spending large sums to build permanent improvements.

This is why large-scale projects, which attempt to build entire sections of cities all at once, can easily go awry. For this reason, Jacobs-inspired planners prefer to develop incrementally, building off of what is working and "what is actually happening." They look for existing "desire paths" and experiment with temporary pilot projects before spending large sums to build permanent improvements.

Although some of the stated aims of the DRI are to encourage "walkability" and to foster "complete streets" downtown, concepts that are actually derived from Jacobs' writings on cities, it is clear that city and state officials haven't read any of her work closely, because in order to quickly lay the groundwork for the city center project, they plan on quickly dealing with 320 parking spaces at the site that stand in the way. Rather than treating the issue of replacing parking as an issue of organized complexity--which requires carefully studying who will be positively and negatively affected by the change and incremental implementation--the city and its parking consultants are attempting to replace all of the municipal lot's spaces all at once by adding surface parking spots in other points downtown. The city and state are throwing caution to the wind despite the fact that the city's nearly completed parking study indicates it is regularly at ideal occupancy and that Plattsburgh is more car dependent than any other city in the region and even more so than the national average.

As the public has started to express concerns over the proposed parking plan's impact on small businesses and circulation in general, some city officials have chosen to respond in a way that appears to be inspired by but completely misinterprets Jacobs' work, stating that Plattsburgh should get with the program and get used to walking more like people do in Burlington or New York City. If only the matter was so simple. The problem is, these places have a much greater diversity of uses that are highly concentrated making it easier and more pleasant for people to walk around for extended periods of time than to drive, whereas Plattsburgh does not. As the history of pedestrian malls in the U.S. shows, making people walk further to get to places of business in downtowns that lack a high degree of vitality and sufficient diversity of uses has driven stores out of business and hurt property values as people have preferred to stay in their cars and drive to the suburbs to spend their money instead; this is why pedestrian malls have an 89% failure rate. According to Jacobs, we can't simply will increased pedestrian activity into existence because "consideration for pedestrians in cities is inseparable from consideration for city diversity, vitality and concentration of use. In the absence of city diversity, people...are probably better off in cars than on foot. Unmanageable city vacuums are by no means preferable to unmanageable city traffic."

|

| Examples of Successful Pedestrian Mall Removals, from "The Experiment of American Pedestrian Malls" |

Yet, in their desire to quickly convert Plattsburgh's municipal lot to a private development, the city and state don't seem to be concerned at all about the strong potential for collateral damage resulting from an all at once, top-down plan to replace the city's most important source of parking. Certainly the mayor isn't; despite being an urban economist who should know better, Read has advocated for pedestrian malls in Plattsburgh for some time. Furthermore, it's telling that, although the mayor has continued a long tradition of granting assessment reductions to large property owners to avoid the costs of litigation despite promising otherwise, the mayor seems perfectly willing to take the risk and do legal battle with small businesses and smaller property owners that will likely be harmed as a result of the parking rearrangement despite being put on guard by local developer Neil Fesette in an email almost a year ago:2

I am suspicious that once the traffic study is done, we will learn that there isn't a nearby parking option that will appease the owner/tenants who currently utilize the City parking lot. I am curious if the City can legally make changes to the current situation without subjecting themselves to the risk of being sued by the property owners I've referenced?

Fragility versus Resiliency

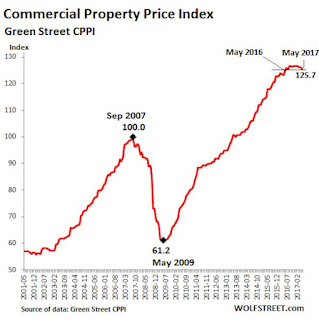

Second, large developments like the proposed city center project are generally fragile; they are usually conceived in good economic times and are developed with the overoptimistic assumption that the statistical trends of the present era will continue or improve well into the future. As such, they are not resilient in the face of substantial social and economic changes such as economic downturns. |

| From Nassim Taleb's "Fourth Quadrant: A Map of the Limits of Statistics" |

|

| Source: "The next asset bubble is so big that even the Fed is starting to take note" |

Consider two examples from Plattsburgh's recent past: A little over a decade ago, the city and the state dove headlong and invested $1.3M into what is now referred to by local residents as "the parking lot to nowhere" in anticipation of a $14M lakefront hotel and conference center that was going to reinvigorate the city. At the time, Mayor Kaprazak stated: "Anytime someone can do something like this to help the city, we will help them." Then 2008 hit and the project never materialized. Years later, as the city wrestled back the waterfront real estate that it had leased to the developer for 99 years, the developer explained why the project never came to fruition: "It was the economy as much as anything. The Upstate economy just never came back." It's ironic that as the next recession nears, the city's current overoptimistic plans to develop a city center on Durkee Street rely on using the parking lot to nowhere, a testament to the failure of large scale top-down planning, to reshuffle parking downtown (actually, the parking study's proposal to use the parking lot to nowhere as the main lot while the city center parcel and new downtown surface parking spaces are under construction is probably the most damaging component of the plan. People will be expected to either walk a half mile through a veritable dead zone to get to downtown or wait for a shuttle).

Similarly, in 2007, a developer forged ahead with plans to develop College Suites, a $23M student housing complex. The developer ended up going bankrupt as the economy tanked and student enrollments declined and never fully recovered. The property ended up being acquired at around half of its construction cost by an investment firm called Stabilis, which has earned a reputation in New York City for "predatory equity," siphoning profits off of distressed properties in low-income minority neighborhoods by not maintaining them. Worse still, when Stabilis was actively pursuing foreclosing on the developer, the City of Plattsburgh, citing fiscal pressures and preferring to avoid litigation, cut a deal with the developer to receive back property taxes in exchange for a 56% reduction in the property's assessment, from $12M to $5.3M; this profit-boosting cost reduction was passed on to Stabilis, providing them with additional capital to pursue predatory equity in the Big Apple and beyond.

Meanwhile, during the same time frame Plattsburgh's older mixed use buildings, which are admittedly a little rough around the edges due to disinvestment downtown over the decades, maintained their value throughout the Great Recession. Some tenants may have come and gone and some of the buildings' uses may have changed, but the properties remained resilient. For example, the block of 11 buildings on City Hall Place and Bridge Street together are currently assessed at three times the value per acre as the College Suites property; even if the College Suites assessment returned to its original $12M figure, this block of buildings is still worth 35% more per acre--and there is a lot of room for upward movement given that the average building in the group is currently assessed at $227,000.

1)

Cuomo's economic development agenda, which also centers around large-scale projects, has had far more failures than successes, even though it is the most expensive of any state in the nation, amounting to 3.5% of gross state product, or 2.5 times more than the average state spends. Despite massive taxpayer investments into upstate's economy primarily in the form of tax incentives for big businesses and large scale projects that leverage lots private investment like the proposed city center project in Plattsburgh, there is little evidence that it's working, as job growth upstate--the primary objective of the program--has trailed neighboring states and the nation.

Meanwhile, during the same time frame Plattsburgh's older mixed use buildings, which are admittedly a little rough around the edges due to disinvestment downtown over the decades, maintained their value throughout the Great Recession. Some tenants may have come and gone and some of the buildings' uses may have changed, but the properties remained resilient. For example, the block of 11 buildings on City Hall Place and Bridge Street together are currently assessed at three times the value per acre as the College Suites property; even if the College Suites assessment returned to its original $12M figure, this block of buildings is still worth 35% more per acre--and there is a lot of room for upward movement given that the average building in the group is currently assessed at $227,000.

Wrapping up our brief tour of Plattsburgh maldevelopment, we've opened up onto another way to develop and improve the city's financial position without risking collateral damage caused by oversimplified top-down planning or even outright cannibalization as we saw in part one. As we've seen throughout this series of posts, such collateral damage will hurt property values and undercut any gains made by a new development. Furthermore, this other way to develop makes the city more resilient rather than more fragile, because, to use the same example, if one building in a block of eleven fails, it is relatively easy to recover without much harm to the community or the city's finances. On the other hand, if the city center project fails or falters, the community will be harmed and the city--which is staking so much on a big gamble--will remain trapped in its age-old cycle where fragility leads to maldevelopment and maldevelopment leads to more fragility. Unfortunately, this incremental alternative that I'm pointing towards and will have occasion to elaborate upon in future posts is not as flashy or amendable to gubernatorial ribbon cuttings as large-scale development, and so our city seems poised to repeat its past mistakes and make itself more vulnerable than ever to shock treatments in the future.

In the case of Poland's shock treatment in 1989, we have the benefit of hindsight and can ask: Was the shock doctrine worth the pain in Poland? It was certainly worth it for a small minority of the population that profited enormously off of the privatization of state-owned enterprises, and the economy eventually did stabilize somewhat after the shock treatment precipitated a full blown recession in Poland that lasted for two years. For many though, things got worse and stayed that way as both unemployment and poverty rates increased substantially and remained high for well over a decade. After about a year and a half of the shock treatment, the public stopped giving Solidarity a free pass and began protesting in large numbers. When national elections were held again in 1993, the party lost dramatically. The people had put an end to their country's shock doctrine agenda.

Yet, we don't need hindsight from a world away and from a different era to show us that the shock doctrine won't work in Plattsburgh. We can see with our own eyes what works and doesn't work in our own city, all we have to do is look closely. For, in the words of Jane Jacobs, "everybody can be as aware as possible of what is actually happening."

1)

Cuomo's economic development agenda, which also centers around large-scale projects, has had far more failures than successes, even though it is the most expensive of any state in the nation, amounting to 3.5% of gross state product, or 2.5 times more than the average state spends. Despite massive taxpayer investments into upstate's economy primarily in the form of tax incentives for big businesses and large scale projects that leverage lots private investment like the proposed city center project in Plattsburgh, there is little evidence that it's working, as job growth upstate--the primary objective of the program--has trailed neighboring states and the nation.

Furthermore, consider economic development in the North Country. NCREDC was formed in 2011, a little into the beginning of one of the national economy's longest upward climbs on record. Despite this, and despite an unprecedented $550M in "regular" public investment into job creating projects during this timespan, (this doesn't even include special public funding for projects like Norsk Titanium, which alone has amounted to $125M, and so far has generated 110 jobs or $1.1M per job), the North Country has actually lost jobs, wages haven't kept up with inflation, and poverty is on the rise. The same is the case for the manufacturing sector, which has been NCREDC's major focus; the sector has also lost jobs and wages have lagged even further behind inflation. Even still, rather than face the facts and admit that this approach to development isn't working, economic developers and governmental officials throughout the region prefer to point to the next golden ticket around the corner, the same corner where the next recession, which is considerably more likely, awaits.

|

| Source: NY Dept of Labor Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) |

2)

Comments

Post a Comment